Edwin

The story of my great-uncle Edwin, a life cut tragically short by war

Exactly 85 years ago, on 27th May 1940, while the eyes of the nation were turned to the events unfolding on the beaches at Dunkirk, six RAF aircraft set out from Shetland to patrol the Norwegian coast, but only five returned. The three-man crew of the missing aircraft included my great-uncle Edwin; he was just 19 years old.

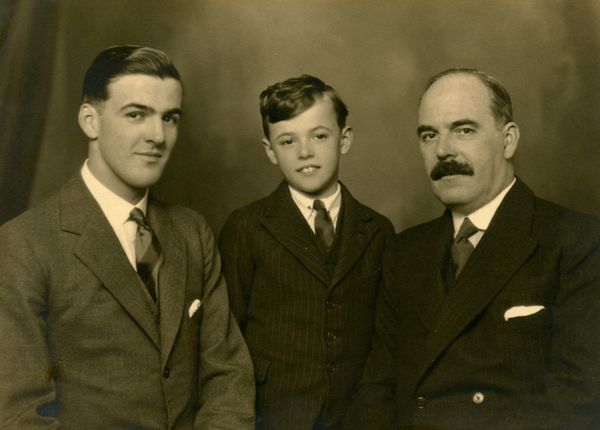

Edwin Holbrow Alexander was born in 1920, the youngest of the five children (three girls, two boys) of Herbert George Alexander and his wife Annie Georgina. Herbert had enjoyed success for many years as a renowned grower and cultivator of orchids (one of the most famous hybrids is named Cymbidium Alexanderi after him), and managed the collection at Westonbirt, near Tetbury, Gloucestershire. He sat alongside his employer, Sir George Holford, on the Royal Horticultural Society’s orchid committee; and on Sir George’s death in 1926 he bequeathed the entire orchid collection to Herbert.

The future looked bright for the family in the 1930s. Edwin’s older brother Stanley (ten years his senior) was already involved in the family horticultural business, which was flourishing, and he was being lined up to take over the reins; but the outbreak of war in 1939 would change everything.

With war on the horizon, Herbert’s sons both joined up. Stanley, who had already served four years from 1933 to 1937 in the Royal Gloucesterchire Hussars, re-enlisted to the Gloucestershire Regiment in May 1939. Edwin, still only 18, was granted a short service commission as Acting Pilot Officer (the lowest ranking commissioned officer) in the Royal Air Force on 29th April 1939.

After the outbreak of war, Edwin was moved on 6th November 1939 to the RAF’s active list as a Pilot Officer, and was assigned to 254 Squadron. 254 had at the start of the war been re-formed as a coastal fighter unit, based at Stradishall in Suffolk, carrying out coastal patrols and convoy escorts along the east coast, later adding reconnaissance and fighter escort.

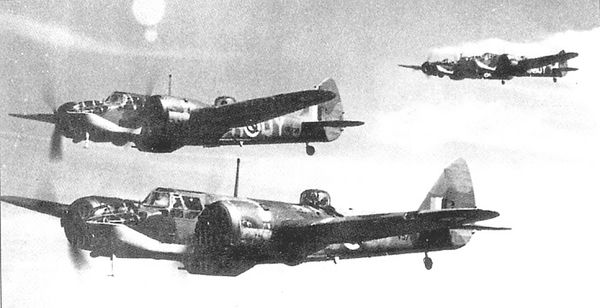

The squadron was equipped with Bristol Blenheim IVF fighter-bombers which, although dating from the mid-1930s, had already been rendered mostly obsolete by advances in technology in the intervening years. Originally designed as bombers, they had been retro-fitted as three-seater fighters; but they were overly susceptible to enemy fire, both from ground and air, and would later be switched to service as night fighters, where they were less vulnerable to high-performance planes such as the Messerschmitt 109.

On 16th May 1940, the squadron relocated to RAF Sumburgh in the Shetlands - today the island’s airport, but at the time little more than a grass strip. The following is taken from an account by Wing Commander H.C. Randall DFC, in his memoir Moths to Mosquitos. Based on the date in his account, he would probably have known Edwin (although maybe only briefly).

On the 25th May 1940, I was posted to the most northern airfield at which I was ever to be based – Sumburgh in the Shetland Islands. As well as my most northern posting, it also marked a new low in standards of accommodation. No. 254 was the first Squadron to have been posted here, though there had already been a flight of Gladiators intended for the island’s own defence. The runways had only just been finished, though the same could not have been said about some of the buildings. In fact we were to sleep under canvas.

The mess was a large marquee, and the bar was constructed from empty wooden boxes, each of which had previously been used to transport two 4-gallon petrol canisters. These petrol canisters were the only source of fuel for our Blenheims and worse still, was the fact that the planes had to be completely refueled by hand! Initially the fuel had to be filtered through chamois leather to remove excess water. The boxes soon became the principal, and sometimes only, source of furnishing on the airfield. They were used in the tents as bedside cabinets, chairs and other useful things.

As an airfield Sumburgh was not ideal. At one end of the runway you had Sumburgh Head itself, and at the other you would approach over the village itself down a slope. The short runway had the sea at both ends. Although we were there in the summer and the sea was so close, no one swam as the water was far from warm. I have to admit to attempting a paddle once, but this was rapidly given up as a bad idea! There also seemed to be a perpetual wind at Sumburgh. You were always aware of the sound of empty petrol tins being blown round the airfield. Later when Nissan huts finally arrived, sheets of airborne corrugated iron replaced the petrol containers!

At 05:30 on 27th May 1940, six Bristol Blenheim IVF from 254 Squadron 18 Group were sent from Sumburgh RAF station in two sections of three to sweep the south-western coast of Norway, mainly in search of enemy airfields, but also to locate the auxiliary naval vessel Königsberg (although records seem to show that it had already been sunk the previous month).

Blenheim R3624 (QY-M) was crewed by Edwin and two others: Sergeant Basil A.J. Henrick (also 19) and Sergeant Thomas P.N. Hammond (23). Near Stavanger on the Norwegian coast they were engaged by the enemy, and Edwin’s aircraft was shot down by the Messerschmitt Bf 109 of Lt. Deuschle of II./JG77 (although it was also claimed by Hptm. Lang). It is strange to think that, in a conflict where so many died, aerial combat was still so personal and one-to-one that it is possible to know the name of the pilot who shot Edwin’s plane down.

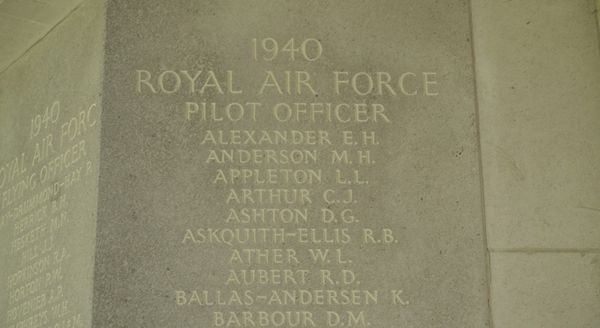

Coastguards reported that an aircraft had crashed into the sea, and the Thurso lifeboat was launched - but no trace was ever found and the men were reported as missing. Edwin is commemorated, alongside so many others, at the RAF memorial at Runnymede.

The loss of Edwin hit the family hard. The following is an excerpt from a letter, written just a couple of weeks later, from my grandmother Vanda (one of Edwin’s sisters) to her brother Stanley:

Didn’t you think the letter to Pa from Bertie’s squadron leader was grand. He was always just Bertie to everyone – none of this terrible side one sees on some officers! I think even the Germans will fall for him – I feel he must be a prisoner Stan don’t you. I mean anyone as grand as Bertie and so straightforward & honest just couldn’t be sent out of this world so quickly. All I hope is that if he is a prisoner they’ll treat him decently – I’ll never never give up hope that he’s not alive, ‘cos it seems quite impossible to me. Doesn’t it seem like that to you?

And she really never did give up that hope: she always believed that somehow one day he would just walk through the door.

It was not, alas, the only wartime loss to be suffered by the family. On 24th September 1944, in the push across Europe after the D-Day landings, Edwin’s brother Stanley (now a Major in the Reconnaissance Corps) was leading a forward recce mission near the town of Mierlo in the Netherlands, when his jeep hit a landmine by the side of the road, and he was killed. He was 34, with two young sons - one aged two, the other only 2 months. He is buried at the war cemetery in Mierlo.

Herbert George Alexander was devastated by the loss of his two sons, and with them the future of the orchid business into which he had invested so much of his life. In their memory he dedicated a pair of stained glass windows at Westonbirt church (now privately owned by Westonbirt School), bearing the insiginia of the Reconnaissance Corps and the Royal Air Force, and with the inscriptions:

Be thou faithful unto death and I will give thee a Crown of Life

and:

To the Glory of God and in loving and grateful memory of Major Stanley George Alexander Reconnaissance Corps killed in action Holland 1944 aged 34 and his brother Pilot Officer Edwin Holbrow Alexander RAF killed in action over Norway 1940 in his twentieth year. Erected by their father and family.